The long weekend presents a little more time and space in which to step away. In my case, that often means taking some time to catch up on reading for pleasure. While I like to read prior to falling asleep each night, I usually only manage a page or two. This past weekend, I was afforded that time.

St. Clement’s has launched an Alumnae Book Club this year which will see Ruth Griffiths, Julia Scott, Patricia Westerhof and Joanne Thompson, four of our retired English teachers, lead different evenings throughout this year.

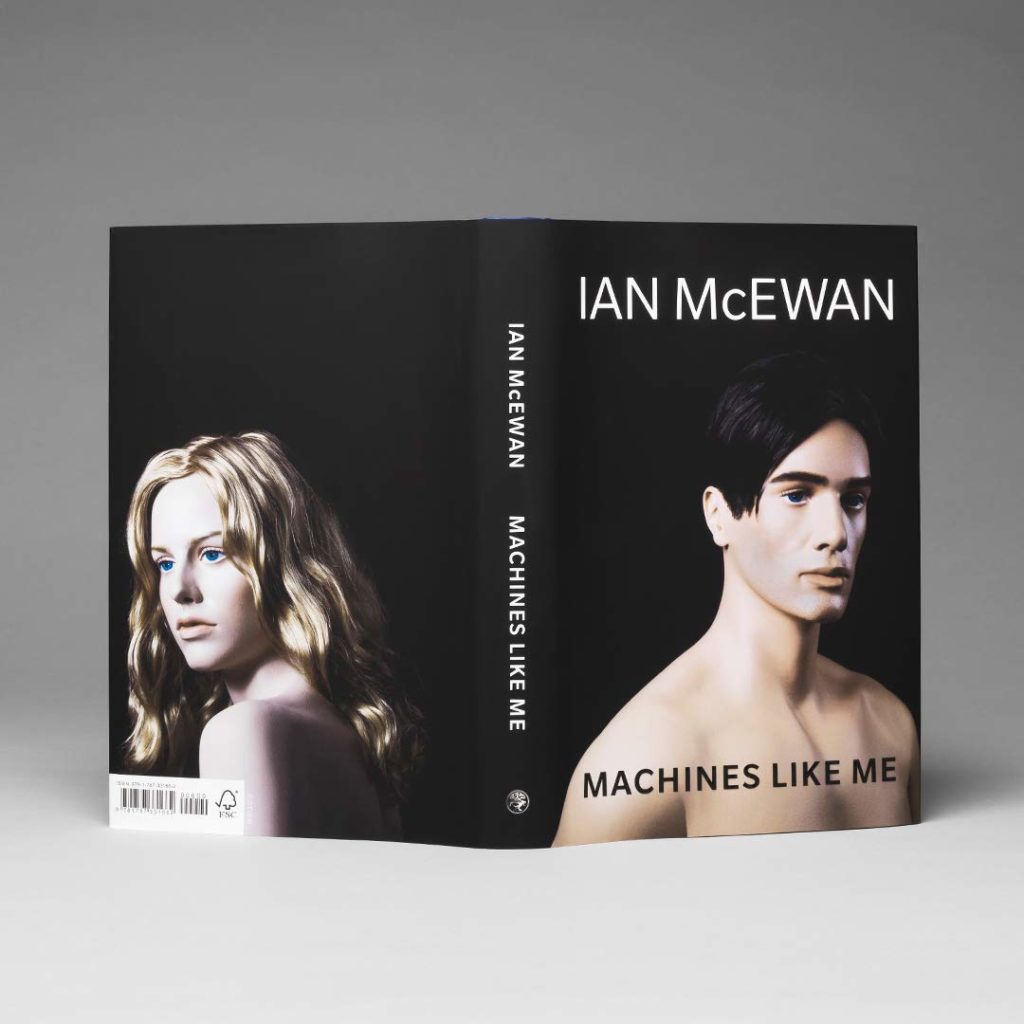

Our first evening is on November 21 led by Ruth Griffiths when we will be discussing Machines Like Me by Ian McEwan and this was my weekend to read it. This is a fascinating and provocative novel that takes place in ‘alternative 1980s’ in the UK during a politically-charged time. Charlie, the main character, purchases what is referred to as a ‘synthetic human’ whom he names Adam. Adam lives alongside Charlie and his eventual partner Miranda. There are several story lines that unfold in this novel; however, what I found most provocative was McEwan’s portrayal of Adam, the synthetic human and how it brings to question the role of artificial intelligence; the reader is challenged to consider the tensions involved with artificial intelligence (AI.) While we often hear and read of fear about where AI may ultimate take us as a civilization, there is also much to consider about the unique and powerful capacities to thinking that humans- and particularly youngsters possess.

At one point, early on in the novel, Adam suggests to Charlie that, “The implications of intelligent machines are so immense that we’ve no idea what you- civilization, that is- have set in motion.” A provocative and early warning to the reader.

While artificial intelligence is one that can intimidate and / or excite people, Machines Like Me evoked a consideration of the opportunities in addition to the worries. In a conversation that Charlie has with Alan Turing, the famous English mathematician, computer scientist, and philosopher, Turing reminds the reader of the power of imagination and, in particular, of that in children that machines has yet to replicate.

Turing says to Charlie, “This intelligence is not perfect. It never can be, just as ours can’t. There’s one particular form of intelligence that all the A-and-Es (Adams and Eves) know is superior to theirs. This form is highly adaptable and inventive, able to negotiate novel situations and landscapes with perfect ease and theorise about them with instinctive brilliance. I’m talking about the mind of a child before it is tasked with facts and practicalities and goals. The A-and-Es have little grasp of the idea of play- the child’s vital mode of exploration.”

A provocative read- and a reason, in my mind, to be hopeful that there are so many opportunities to celebrate and encourage our children’s imagination and play, while also leveraging the advantages that AI provides us.